PARSI, JEWISH & ARMENIAN WOMEN

An extract from PERSIAN WOMEN & THEIR WAYS

THE EXPERIENCES & IMPRESSIONS OF A LONG SOJOURN

AMONGST THE WOMEN OF THE LAND OF THE SHAH

WITH AN INTIMATE DESCRIPTION OF THEIR CHARACTERISTICS,

CUSTOMS & MANNER OF LIVING

by COLLIVER RICE

WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS & A SKETCH MAP

London Seeley, Service & Co. Limited 196 Shaftesbury Avenue 1923:

pp. 22-37, CHAPTER II

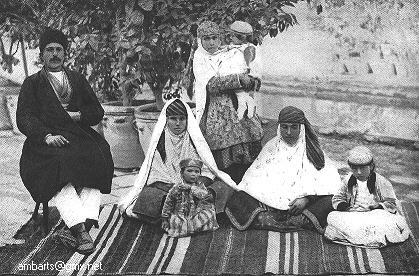

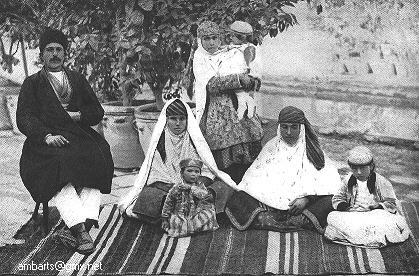

A Parsi and his Wife and Children.

This man was gardener to the Telegraph Director in Yezd. The flower pots contain orange trees. The rug is a gilim (p.25).

THE Parsis or Zoroastrians are the sole survivors of the pure Iranian or Persian race. Parsi is a word akin to Persian, and refers to race. Zoroastrian, a follower of Zoroaster, refers to religion. The actual period when Zoroaster lived is unknown; in all probability it was between 1000 and 700 B.C. The faith he taught was the national religion of Persia for many centuries. The Magi who followed the star to Bethlehem were probably Zoroastrians. Many of their sacred writings are said to have perished in the burning of Persepolis, but Pliny, in the second century, speaks of two million verses as being still extant! Making allowance for this generous computation, Zoroaster must have handed down a perfect storehouse of teaching to his followers.

Until the Arab invasion in the seventh century this had long been the dominant faith of Persia. When the creed of the Prophet was forced upon the country, many had no choice but to accept it; others, unwilling to change their faith, left their native land and settled in India, and only a small remnant held both to the faith and to the land of their fathers. Hence the wealthy and prosperous Parsi settlements in India to-day, and the remnant of about 9000 found in Yezd and Kirman and the surroundmg villages in Persia. Here they have the character of being honest, industrious, intelligent, truthful, moral, (23 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) and better than their Moslem neighbours, with whom they never intermarry. In Yezd they have a large quarter of their own, with cleaner and wider streets than are found in the Moslem part of the town. They have good gardens and well-kept land, as agriculture was in the past upheld by their religion. Some are engaged in the silk industry and in husbandry, while many are merchants. In the Zend Avesta, their sacred book, it is written that "whoso cultivates barley, cultivates righteousness," but at present they are more a commercial than an agricultural people.

Their belief is still in the conifict between good and evil. The world is looked upon as the battle-field of two contending spirits, eternal and creative in their origin and action-the great wise God Ormuzd, or Ahura Mazda, and the wicked spirit Ahriman. The conflict is not believed to be hopeless nor is it destined to be perpetual. The light, the sun, the fire are the symbols of Ahura Mazda; therefore the sacred fire is always burning in their temples, and when they pray they face the sun. The name "fire-worshipper" is a misnomer; they do not worship the sun or the fire, but the One whose presence and character these symbolize. The sun in the Persian symbol is a relic of the past when it was the emblem of the so-called "fire-worshippers."

In many ways there is wide divergence between the teaching of Zoroaster and the religion as now practised. His followers claim to be monotheists and object most strongly to any change of religion either in the way of conversion to Zoroastrianism or perversion from it. They claim that the only way to be a Parsi is to be born of Parsi parents. Their faith seems to be the one thing that holds them together. Yet in Persia many are being strongly influenced by Bahaism, of which more later. (24 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women)

A practice of which they are very tenacious is the investiture with the sacred thread, and in many cases also with the sacred shirt.

Boys and girls at about the age of twelve are invested with these before a solemn assembly and are forbidden ever to lay them aside. To walk even a few steps without them is an unpardonable sin.

Another binding custom is the disposal of the dead, burial, as defiling to the earth, being abhorrent to the Parsi. Dakhrnehs, or towers of silence, are built outside the cities. No one but the professional bearers of the dead may enter these towers. The upper part of the tower is reached by a winding road or stairway, and at the top there are gratings "clothed with the light, facing the sun," on which the bodies are placed. Here birds of prey quickly dispose of the flesh, and in time the bones fall through into the central pit below.

In Persia the Parsis long laboured under many disadvantages. They might not build their houses as high as those of the Moslems. They might not ride through the town. The style and colour of their clothing was also restricted.

Parsi women until recent years were uneducated and ignorant. Now education is desired for them. The English school for Parsi girls in Yezd is largely attended, and the Parsis themselves have opened another. Dari, an unwritten language, is chiefly spoken by the women, who do not readily understand modern Persian.

Marriage with next of kin is not permissible. Polygamy is unknown.

The women wear baggy trousers which reach to the ankles; over these they have long full coats; coloured handkerchiefs are worn over the head and a chădar folded like a shawl. The skirt and trousers are (25 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) usually made of material with very broad stripes of bright colour. Many of their clothes are made of the silk which is woven in Yezd.

The following account of a Parsi wedding was written by an English lady who was present: -

I went for part of a Parsi wedding, the

bride being one of Miss B.'s schoolgirls, a very bonny girl of

fifteen. The guests had assembled at I P.M., and the afternoon

had been spent in talking, playing the timbrels, tea, and sweet-eating

till 5 P.M., when the groom's best man came with a number of

friends bearing four large wooden trays, one full of apples,

pears and pomegranates for the bride's male relations; one with

bread and a kind of sweet for which Yezd is famous, which looks

like spun glass or raw silk; the third contained the bridal dress

provided by the groom; the fourth loaves of sugar for the bride

and the members of her family. The bread and sweets were handed

to the guests, and when the men retired the bride was adorned for

her husband in bloomers and a flowing robe of green and cinnamon

silk, with a long sort of jacket of cloth of gold; a green silk

shawl for the head was fastened by a heavy gold ornament on the

forehead, and from it hung many gold coins. Silver bangles, a

gold ring set with an emerald, and a very handsome talisman, the

size of a breakfast saucer, in bas-relief representing Zardushti

(the Parsi prophet), the sacred fire and various scenes in his

life-these two were suspended on a silver chain with two

talismans like snuff-boxes containing the Zardushti prayers. Then

all the friends in turn saluted the bride and offered a sprig of

myrtle and a pomegranate (typical of life and fruitfulness): this

was nearly over when I arrived. Then the timbrels began. Everyone

laughed their loudest and talked at the tops of their voices (no

one seemed to (26 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) attempt to

listen) till 8.30, when a thundering knock brought silence and a

scrimmage for chadars, for the best man and his friends had come

to ask the bride if she wished to marry the groom! The green silk

shawl was spread over her as if she were asleep. The men came

near, and the best man, in a stentorian voice, asked: 'Do you,

Goher, child of Shireen (sweet) and Khuda Parast (God-worshipper),

wish to marry Mehriban?' The bride did not reply. The man faced

his friends, 'She did not answer,' upon which they all yelled to

wake her. Eleven times this was repeated, louder and louder, till

the bride said 'Yes,' which was the signal for shouts of joy and

a headlong rush to tell the groom. A minute later the bride's

father came from an inner room carrying a large bundle, the groom's

clothes, which the bride presented. To fill up time the timbrels

were again brought out, and about an hour later the groom arrived,

and tea was served to him and his friends, then to the bride and

women, and the procession was formed, preceded by lights,

timbrels and the dowry, to go to the groom's house. Every few

minutes the bride stopped and said: 'I will go no farther till

you pay my way.' Each time, after a good deal of argument, the

groom gave her money, which goes towards the cooking utensils

which she has to provide. At the house the priest was waiting

with a pan of sacred sandalwood fire, round which all the company

walked three times. Then the husband led the bride into the side

room, and all the women who had come with her stood round the

room. The bride and bridegroom sat down on a handsomely covered

mattress, and then his sister and her mother uncovered her face.

Next they took off their right socks and put their feet together;

some water was brought, and the groom washed first his foot, then

hers, (27 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) then his right hand,

then hers, then his own face, then hers. A large glass of sherbet

was brought, which he sipped and she finished. Then he produced a

large black silk handkerchief with coloured border, to dry their

faces, hands and feet. Then all the company said, 'May your eyes

be enlightened, may you live a hundred and twenty years,' and

left the couple to wedded bliss. The only religious ceremony is

at the groom's house, where the bride's best man is her proxy,

and is married to the groom, while the priest's boys ring little

silver bells and the priest mutters prayers."

I went for part of a Parsi wedding, the

bride being one of Miss B.'s schoolgirls, a very bonny girl of

fifteen. The guests had assembled at I P.M., and the afternoon

had been spent in talking, playing the timbrels, tea, and sweet-eating

till 5 P.M., when the groom's best man came with a number of

friends bearing four large wooden trays, one full of apples,

pears and pomegranates for the bride's male relations; one with

bread and a kind of sweet for which Yezd is famous, which looks

like spun glass or raw silk; the third contained the bridal dress

provided by the groom; the fourth loaves of sugar for the bride

and the members of her family. The bread and sweets were handed

to the guests, and when the men retired the bride was adorned for

her husband in bloomers and a flowing robe of green and cinnamon

silk, with a long sort of jacket of cloth of gold; a green silk

shawl for the head was fastened by a heavy gold ornament on the

forehead, and from it hung many gold coins. Silver bangles, a

gold ring set with an emerald, and a very handsome talisman, the

size of a breakfast saucer, in bas-relief representing Zardushti

(the Parsi prophet), the sacred fire and various scenes in his

life-these two were suspended on a silver chain with two

talismans like snuff-boxes containing the Zardushti prayers. Then

all the friends in turn saluted the bride and offered a sprig of

myrtle and a pomegranate (typical of life and fruitfulness): this

was nearly over when I arrived. Then the timbrels began. Everyone

laughed their loudest and talked at the tops of their voices (no

one seemed to (26 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) attempt to

listen) till 8.30, when a thundering knock brought silence and a

scrimmage for chadars, for the best man and his friends had come

to ask the bride if she wished to marry the groom! The green silk

shawl was spread over her as if she were asleep. The men came

near, and the best man, in a stentorian voice, asked: 'Do you,

Goher, child of Shireen (sweet) and Khuda Parast (God-worshipper),

wish to marry Mehriban?' The bride did not reply. The man faced

his friends, 'She did not answer,' upon which they all yelled to

wake her. Eleven times this was repeated, louder and louder, till

the bride said 'Yes,' which was the signal for shouts of joy and

a headlong rush to tell the groom. A minute later the bride's

father came from an inner room carrying a large bundle, the groom's

clothes, which the bride presented. To fill up time the timbrels

were again brought out, and about an hour later the groom arrived,

and tea was served to him and his friends, then to the bride and

women, and the procession was formed, preceded by lights,

timbrels and the dowry, to go to the groom's house. Every few

minutes the bride stopped and said: 'I will go no farther till

you pay my way.' Each time, after a good deal of argument, the

groom gave her money, which goes towards the cooking utensils

which she has to provide. At the house the priest was waiting

with a pan of sacred sandalwood fire, round which all the company

walked three times. Then the husband led the bride into the side

room, and all the women who had come with her stood round the

room. The bride and bridegroom sat down on a handsomely covered

mattress, and then his sister and her mother uncovered her face.

Next they took off their right socks and put their feet together;

some water was brought, and the groom washed first his foot, then

hers, (27 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) then his right hand,

then hers, then his own face, then hers. A large glass of sherbet

was brought, which he sipped and she finished. Then he produced a

large black silk handkerchief with coloured border, to dry their

faces, hands and feet. Then all the company said, 'May your eyes

be enlightened, may you live a hundred and twenty years,' and

left the couple to wedded bliss. The only religious ceremony is

at the groom's house, where the bride's best man is her proxy,

and is married to the groom, while the priest's boys ring little

silver bells and the priest mutters prayers."

The Jewish element, though alien, has been in Persia since the Babylonian captivity. In most of the large cities there is a distinct Jewish quarter which, bad as some parts of a Moslem city may be, is sometimes worse. Many of the trades followed by Jews are those which Moslems will not touch.

The Jewish women are not veiled, but they adopt the black outdoor chadar worn by all Persian townswomen and keep their faces well covered. In their own houses they wear moderately long full skirts, with a jumper-like upper garment and a jacket. A muslin square folded cornerwise is worn over the head and pinned under the chin. Their hair and eyes are mostly dark, but bright auburn hair is sometimes seen, and there are many very pretty children with regular and beautiful features. Speaking generally, they are affectionate and intelligent, hard-working and painstaking. Language is easy to them. Hebrew is the language of their worship, and Persian of their everyday intercourse with the Persians, and English and French are looked upon as leading to advancement and money-making.

Many are educated at the French and English and (28 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) American schools, and it is a common thing for a Jewish girl to go to a Moslem anderűn to teach French to Persian ladies.

The girls are betrothed when they are very young, eight or nine, but not married until they are about sixteen, and as a rule there is no great disparity in age between husband and wife. Most of the family names are familiar as Bible ones, as Ezra, Eliahu, Juseff, Isaac, Manasseh, and so on; and among the women there are a good many Esthers and Saras and Batias; but there are also such names as Taous, meaning peacock, Murvared, meaning a pearl, Shushani, meaning lily, as well as names which may be considered Persian, such as Sultanat, Kishva, Nosrat and Kafi. The latter means "enough," and is often given when a boy would have been a much more welcome arrival than a girl. This, of course, is almost always the case in the East, and so the name is often given, but one is sorry for the bearer of the name.

Many Jewesses do beautiful embroidery; others make cotton tops for shoes, while in Yezd a large number of wornen are employed in silk-carding.

There are various places of pilgrimage, and Jewesses are often met with on the way to these shrines. For instance, there is a shrine some fifteen miles from Isfahan said to be the burial-place of "Lady Esther "-not the queen, as her tomb is at Hamadan. There is a large burying-ground attached, and the tanks and flowing water which are prescribed for the ceremonial washing of the dead. No Jewish interments take place in the city, and very pathetic are the processions out to this nearest burying-place.

Though Persians have never persecuted the Jews, they treat them with the utmost contempt. (29 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women)

The Parthians, Medes and Elamites who were present in Jerusalem on the day of Pentecost were at the time, or later, subjects of the Persian Empire. In the centuries following, the Gospel was widely preached in the country, and we are told that multitudes became Christians, that churches were built and bishoprics founded. Terrible persecutions followed, and in the fourth and fifth centuries thousands were martyred. But in spite of this, as the Nestorian Tablet in China testifies, the Persian Church sent teachers as far as China and other distant parts of Asia. Nestorians and Armenians came under Persian rule, and to-day there are at least 8o,ooo members of these Eastern churches in Persia.

The best known, to me, of these Eastern Christians are the Armenians. Their ancestors were brought from Julfa, on the Araxes, in Armenia, by Shah Abbas the Great, a contemporary of Queen Elizabeth and one of Persia's greatest rulers. The idea in bringing these 20,000 Armenians was that - they should instruct Persians in the arts and crafts of which they knew much.

A tract of land on the south side of the Zindeh Rud or Living River, on the north side of which lay the then capital city of Isfahan, was given to the Armenians on which to build and settle down; this settlement they called Julfa, after their old home. To-day Julfa is a quiet little place, with narrow streets and high walls, but with a clean and well. cared-for appearance. It has a cathedral and twelve Gregorian churches, also Anglican and Roman churches. Each sect has good schools and education is general. Julfa has several large gates, which are locked at night for safety. Many of the Armenians are wealthy merchants; other are employed in Government offices, banks, merchants’ offlices, (30 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) and so on. Most of the large towns in the country have small Armenian colonies. There are also a number of Armenian villages in Feridan and in Chahar Mahal.

The picturesque national dress is now only worn by elderly women, as the young women and girls wear garments closely approximating to European dress in the house, and out of doors merely the long black chadar as worn by Moslem women over their house dress, but no veil. This chadar will probably disappear before long, as many prefer a coat and skirt, and a long silk scarf wound round the head and thrown over the shoulder; some are even aspiring to hats. Armenians, though, are very conservative, and the older men shake their heads and say that they don't know what the girls are coming to, and that they won't allow their daughters to adopt such advanced modes; but nevertheless the daughters are doing it.

The old-fashioned dress still worn by the older women, ... seen at its very best on high days and holidays, is coloursome, and consists of various long garments, the other one being of beautiful scarlet cloth or cashmere shawl braided and trimmed with fur, and fastened with silver buttons. A heavy loose silver belt always finishes this costume. Gold necklaces, gold or silver beads and many rings are also worn by those who can afford them. A tall head-dress is worn, over which several handkerchiefs are tied, and, most important of all, a triangular piece of white cambric is folded several times and tied round the chick and mouth. Woman's silence before her superiors in sex and age has in the past been as important in an Armenian as invisibility and the covering of her eyes has seen in a Moslem woman. The correct outdoor dress worn with this old-time costume is a white chadar.

The village women still adhere to their old style of (31 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) dress, but wear a large coloured apron, generally of coarse red cotton stuff, and ornamented with white china buttons. The head-dress as worn by villagers is often nearly a foot high, and is swathed with the same red material of which the apron is made, with silver coins and chains twisted in and out. The moutne, or mouth cloth, is also worn, but it is fastened right over the top of the nose and is only lowered for eating. One of these village women as a patient in a hospital bed is a problem for the nurses, as she strongly objects to the removal of any article of attire, especially the head-dress.

There is more home life among the Armenians than among other dwellers in Persia. Marriages are to a great extent arranged by the families, but here again the young people now have many opportunities of meeting, and are taking things much more into their own hands. Armenian brides may be sixteen or eighteen, or older. The betrothal, or, as they often call it, the "engagement," is a festive occasion, with many guests and a great deal of sweet-eating, at the bride's house. With many girls marriage is not looked forward to with pleasure, and behind the scenes there are often tears and many expressions of sympathy from girl friends. When the wedding day comes there are separate festivities at the houses of the bride and bridegroom. At the bride's house there will be a great number of invited guests. Most Armenian houses have long narrow guest~rooms, and for any function there is a large table in the middle of the room laden with cake, fruit, wine, sweets and flowers. Tea is brought in in large cups, on large trays, with milk and sugar. The chairs are generally arranged straight round the room with their backs to the wall. Anything much stiffer it would be difficult to imagine. After a time the bride goes to another room with her (32 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) female relatives and friends, and here, while she changes her clothes, they hover about, holding lighted candles decorated with gold paper. The bride's hair has to be done elaborately, and every garment changed. When she is ready she is very much like an old-fashioned English bride-white brocade, with lace and chiffon, a veil and orange blossom, white gloves and shoes, and a bouquet — but the art of flower arrangement has scarcely reached Persia yet. While she is getting ready the elder members of the family and guests dance in the compound. This dance is a slow, weird movement: the dancers hold hands and move round in a circle, and from time to time hold up various articles of clothing, such as a coat or waistcoat, which are part of the bride's present to the bridegroom. There are always some hired musicians playing on tars and tom-toms. About the time that the bride is ready, vigorous knocking will be heard on the front door announcing the arrival of the bridegroom with his friends. Her nearest male relative, father or brother, must open the door and welcome the bridegroom. The procession will then start for the church, headed by the musicians, who every now and then stop and refuse to proceed until more money is given to them.

I am indebted to an Armenian friend for the following description of the wedding ceremony: -

"The bride and bridegroom attend at the door of the church and await the clergyman, who, dressed in vestments, descends from the altar and meets the pair at the door. He then solemnly explains the meaning of marriage, xplaining in very simple language the duties of both husband and wife. He explains the thorny path of life and how they must bear the burden together, and love night through life for better or for worse, etc. Then (33 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) immediately after he asks the fatal question, to the groom: 'Will you be lord of this woman?' He nods his head and whispers 'Yes.' Then he turns to the bride and says: 'Will you be obedient to your lord?' She nods and says 'Yes.' (But they don't mean it!) The priest asks the question three times, and after receiving an affirmative answer in each case, he blesses them and then invites the pair to go to the altar for the ceremony. If the girl or boy says 'No,' the priest merely tells them to go home without entering the church. I think it's a delightful custom. It is more serious than the custom of the Western churches."

After various prayers and injunctions, part of the bride's veil is put over the bridegroom's head and a silver cross placed over both heads. A sealed green cord is put round the bride's neck and a red cord round the bridegroom's neck; the cross is put into the bridegroom's pocket, where it remains until the priest asks for it. The Armenian Church follows our Lord's teaching about divorce.

After the ceremony the festivities are continued at the bridegroom's house and are often kept up all night. The newly married couple will make their home with the bridegroom's parents. Housework, children, cooking and knitting have long filled a woman's horizon.

Housework means much less there than in England. Women do scarcely any shopping, this being done by the men. Armenian servants in European houses always expect two or three hours off in the afternoon to shop for their own households. AU this means that the women have a good deal of spare time, but they are not idle. Some do most elaborate silk knitting, socks, caps and bags, while the majority knit coarse white cotton socks universally worn by (34 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) Persian and Armenian men. The women of three generations may often be seen standing or sitting at their own front doors knitting. They knit socks and stockings from the toe and go up to the leg. They always use five needles, and hold their cotton with the left hand like the Germans.

Nowadays the outlook of Armenian girls is broadening. In Julfa there are good libraries, and Armenian, French and English books and papers are largely read. They are very proud of their Armenian literature, much of which is the work of Russian Armenians. Many houses have a musical instrument, a harinonium, or a tar, an instrument very like a mandolin. These are made in Julfa. Gramophones are also becoming very general. Armenian music as heard in the churches is not attractive to Western ears; on special festivals such as Easter the choirs are composed of boys and girls, all wearing long straight cotton surplices.

Many Armenian girls in Teheran, Julfa, Isfahan and elsewhere now take up teaching either in private houses or in schools; and numbers have become hospital nurses, some proving themselves most capable and efficient. Many have a distinct sense of vocation and patriotism. The sufferings of their own people in Armenia cut them to the quick, and they are ready to do all that lies in their power to help them. Kindness and practical sympathy are strong traits in Armenian women, and they do much to help poorer relatives and neighbours.

The idea of keeping back bad news is very strange. Supposing a son or husband dies in some other part of the country or abroad, the last people to be told are the nearest relatives. Everyone else in the place may know, but not until a day arrives which has been decided upon by those to whom the news has been (35 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) sent, are the actual family of the deceased told of their loss.

Though the Armenians are home lovers, they are great wanderers. Every spring a large party of men and boys leave Julfa for India, Java, or elsewhere. Numbers of the boys go to Calcutta to school when they are fourteen or fifteen, but almost invariably do they, in later life, come back to Julfa to marry. In many cases the bride will go away with him, but numbers of wives are left with their parents, the husbands. coming back at long intervals.

Visiting is very popular among the Armenians. Most Christian names are those of saints or flowers. Every saint has his or her special day in the calendar, and instead of keeping birthdays they keep what they call name days." There is one day for Mary, another for John, another for John the Baptist, and so on, and when these special days come round you are expected to call on all your friends who have this special name. Christmas and Easter are again great times for visiting. At their Christmas, which falls twenty-six days after ours, there are four or five days devoted to this friendly intercourse.

I have paid as many as a hundred and twelve calls in four days and been most hospitably entertained, eating sweets, and drinking tea or coffee in nearly every house. It is a delightful custom, because everyone is in and ready for visitors, and in a short time it is possible to see scores of one's friends. As soon as you knock, the front door is opened and you are taken into the room which is set apart as the guest-room during the festival. Very often it is a summer room and, so, very cold in January. Sometimes a brazier of hot charcoal is brought in; if not, they always suggest lighting the fire. In the smaller houses where the living-room is being used as the guest-room, it is warmed (36 Parsi, Jewish & Armenian Women) with the kursi - i. e. a pan of charcoal under a low wooden table, the latter being covered with a wadded quilt. In the poorest house sweets and nuts will be ready, and often coffee is being kept hot for visitors. In well-to-do houses there are numbers of plates of sweets and nuts and biscuits on the table, and tea and cake are usually brought in. You first wish that your friend's eed, or feast, may be blessed. Then you have a little general conversation and inquire about all the members of the family, various sweets being offered by different people in turn. The Armenians are fond of being photographed, and in almost every house there are numbers of photographs not only of themselves, but of relatives and friends who are in Java or India, England or America. Very often there is a new wedding or family group to be admired, and all sorts of things commented on. The difficulty is not to find subjects for conversation, but for everyone to get in all they want to say in the necessarily short time which can be spent in each house. As a rule the men go out visiting, and sometimes the girls; the elder women are always at home during all the visiting days of the feast. Most Armenian women know a little Persian; some a little English. I knew Persian and a very little Armenian, and I remember only one visit among hundreds where there was any difficulty about conversation, and in that house they knew only Armenian. I shall always retain the happiest recollections of my dealings with the Armenians of Julfa, especially the women and girls, among whom I have many friends.

Armenian Nuns at St. Katarine's Convent, Julfa

Beating the board as a summons to worship is a relic of ancient times when there were no bells.

The sounds are soft and musical and very much like bells (p. 185).